The Man who Souled the Coffee World: Hermann Sielcken and Brazilian Valorization

Considering current events regarding the stock market, Hedge Fund investors, short squeezing, and community action, I wanted to share a lesser-known story about what started the boom-and-bust coffee cycle from the book Uncommon Grounds by Mark Pendergast.

For most people, coffee is only a beverage. It is not often thought about as the second-most traded commodity (beat out by only oil), and it is even less often thought of as a crop, a cyclical crop with long fruiting times. It takes years for a coffee plant to produce the cherries that the farmers then process into coffee beans. However coffee as a crop with all these defining attributes ruled the Brazilian economy during the late 1800s.

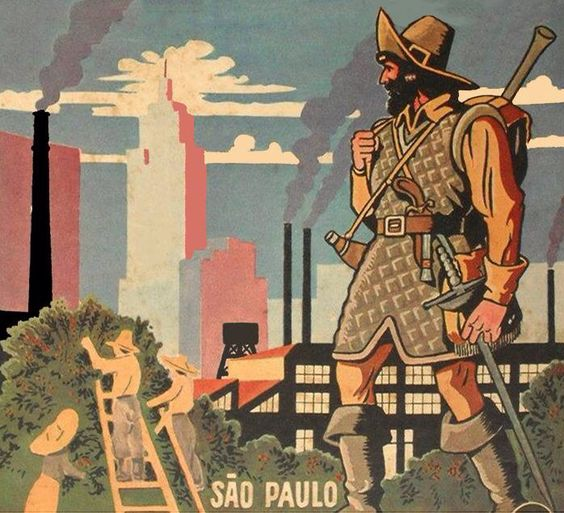

During that time Brazil was far and away the largest producer of coffee in the world, with over 80% of the world’s coffee came from Brazil. Notably Sao Paulo had an established system of farms and production. With the recent abolition of slavery in the country Italian, Spanish, and Japanese immigrants flooded into the country to get a share of the booming coffee industry. Population in Sao Paulo grew over 700% in the second half of the century. Coffee traded for something like .14-.18 cents a pound to the US. Quality of life was improving in the country overall, but we know what happens after a boom.

Many farmers scrambled towards coffee production and the 1896 crop flooded the market with far too high a supply for the demand. Price per pound began trading below .10.

An inflationary monetary policy at the time tanked the value of the local currency, but because coffee traders exchanged for foreign currency in the coffee consuming countries (like USD or the Euro) they had no incentive to stop producing coffee.

A coffee tree can take 3 to 4 years to fruit. So during this time of prosperity, short sighted planting led to a flood in the coffee market so substantial that the price of coffee per pound dwindled to .06. And at the same time Brazil reconciled with their monetary policy and began strengthening the local currency once more, hurting the exchange rate for the coffee traders and creating a real economic and humanitarian crisis.

Valorization

To put it plainly, Brazil was fucked. State representatives from some of the biggest producing areas in the country came together and schemed a way to pull large amounts of coffee off the market to short the supply and ideally raise the price. They called it Valorization. But with the Brazilian government not wanting to be a part of the scheme, they simply couldn’t get enough cash to buy enough coffee off the market to impact the price. That is, until they found Hermann Sielcken.

Sielcken was a self-made German-American man rich as a traveling salesman and eventual partner in the company. He was noted for his ruthless treatment of competitors and market manipulation.

With Sielcken’s own money and his connections with some heavy-hitting financial backers, Sielcken was able to garner a 75-million-dollar LOAN to the syndicate of Brazilian coffee producing states. The terms of the loan were simple:

- The financial backers would pay for 80% of the price of the coffee, and the Brazilian syndicate would pay the other 20%

- Brazil would pay to store the coffee, pay 6% interest on the loan, AND pay 3% commission costs handling the coffee because technically they still owned it

- If coffee prices were to rise above the .07 cents they were trading at during the time then all purchases would stop until the market came back down.

In the words of Hermann Siecklen, it was “the best loan I have ever known.” Over the years as the supply dwindled and as the rippling effects of the post-boom coffee planting took effect, coffee shot back up to .14/lb. And if you’re following along, that means the valorized coffee could now be sold onto the market for over double what the financial backers paid for it, with all that interest, to the tune of nearly 10 million 134lb bags of valorized coffee.

Hermann Siecklen, with not all that much help, had successfully pulled off one of the greatest heists in the history of the financial world. Of course as coffee prices shot up, the coffee consuming countries were in uproar. Even John Muir, the famed naturalist, was pissed off about an, “iniquitous conspiracy between a foreign nation and an American citizen.” The U.S. spent years trying to prosecute Hermann as a monopoly and violating anti-trust laws, but with Hermann’s vast knowledge of coffee trading and ability to shift the focus towards a foreign policy issue, he was able to settle.

Sielcken showed off his considerable wit many times during the lawsuit, with the best instance countering the US Attorney general with,

“I question the propriety of the United States criticizing or going into the details of the action of another country. Supposing that in this country we had a deal on cotton in the South, and Brazil should say, ‘Well, we want to look into that.’ Any foreign government or any foreign party that would act in that way would be thrown out of this country.”

Uncommon Grounds, Mark Pendergast

In the end, Sielcken was forced to sell off most of the valorized coffee he still had in the US, which was kind of his whole point anyway. Fortuitously, he never had to prove how or who he sold it to because the prosecuting Attorney General stepped down at a pivotal point. Which made it really funny after his death, to find out he had sold it to his own company, the Woolson Spice Company.

He may not have been the most ethical man but his actions absolutely saved the coffee industry of Brazil at the time. Without the valorization scheme the price of coffee would have dropped so low that Brazilian farmers would have given up entirely, shorting the world’s coffee supply far more than the valorization scheme did and making the price per lb for guys like John Muir even higher.

So, in a way, we should all be thanking old Hermann. The man who bought and souled the coffee industry.